They had bought the place a few years earlier, having left Manhattan at the height of the pandemic. It was love at first sight. The house was charming, if a bit small, but that didn’t bother them. They figured they’d enlarge it when the time was right. The lot (also small) was situated at the corner of two quiet, tree-lined streets.

It seemed like the perfect place to raise a family. After a tense bidding war, the house was theirs.

By the time their third child was born, the walls were starting to close in. They needed a larger kitchen and a proper master suite—space to breathe, to grow. They spent nearly a year designing the addition, refining every detail. Kathy, who had studied architecture in college and briefly worked in the field in New York, took particular joy in the process. Though she had never gotten her license—choosing instead to stay home full-time when their first child arrived—she poured herself into the design like a pro.

After interviewing several contractors, they chose Clovis Brothers, a highly regarded local firm. Clovis seemed like a perfect fit. Even though the firm wouldn’t be available for nearly a year, John and Kathy decided to wait. “We just really clicked,” John had said.

As Clovis’ start date approached, the couple submitted their construction drawings and permit applications to the town. Then they waited.

A month later, they got the first piece of bad news: the application was incomplete. The building department wouldn’t review the plans until the zoning department approved them—and Kathy had failed to include a site plan and zoning calculations.

Caught off guard, Kathy realized she was out of her depth. Those requirements hadn’t applied to her past projects in Manhattan. She reached out to Jennifer, a former colleague who’d worked on some suburban homes, and asked for help.

Jennifer pored over the survey, the proposed addition, and Princeton’s zoning ordinance. When they next met, her expression was grim.

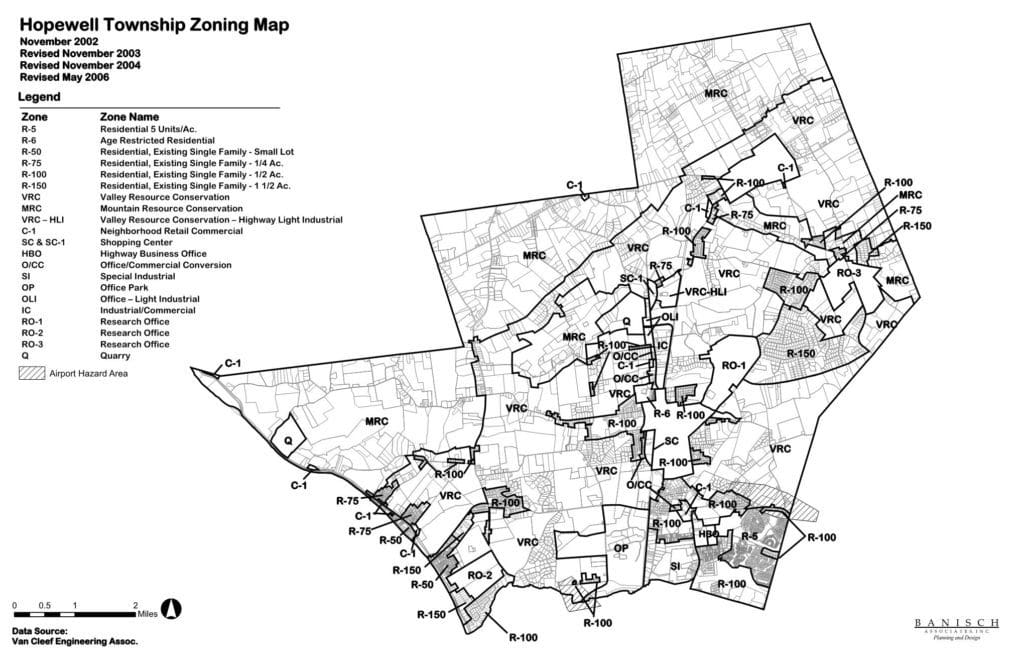

She spread the marked-up plans on the table. The lot, it turned out, was smaller than the minimum required in the zoning district. Not just a little smaller—way smaller. So much so that all four setback lines actually overlapped the existing house. Worse, her calculations showed the house already exceeded the maximum allowed lot coverage and floor area. And that was before the addition.

Kathy’s face blanched. “So… what does that mean?”

“It means,” Jennifer explained, “that your house is nonconforming. You can’t expand it without a variance from the zoning board. If someone built a new, conforming house here today, the footprint would be limited to just 347 square feet.”

Jennifer could only shrug. She suggested resubmitting the plans anyway—maybe the town would be lenient, given the lot’s size. “It seems reasonable, right?”

John and Kathy held on to that hope. They resubmitted. And waited.

Another month passed. Then came a second notice—this one stamped, in bold red letters:

John, usually easygoing, looked stricken.

When they met with the zoning officer, he confirmed what Jennifer had said. Their lot, like so many in Princeton and other historic towns, was legally nonconforming. Hundreds—if not thousands—of homes faced similar issues.

The process for obtaining a variance, he warned, was complex, time-consuming, and costly—with no guarantee of success. At best, it would take three months just to get a hearing. His advice: hire a land use attorney.

John sighed. “That sounds expensive.”

The zoning officer nodded sympathetically.

When they updated Clovis Brothers on the delay, the contractor was understanding but firm. “I can’t hold your spot,” he said. “I’ll keep you on the list, but if this drags on, it could be another year before I can start.”

They didn’t understand the zoning rules, and it cost them dearly—in time, money, and frustration.

This happens more often than you’d think. Many homeowners and buyers (and even architects) dive into design without knowing what can actually be built on a property.

300 Witherspoon Street, Suite 201, Princeton, New Jersey 08542

609.737.6444

© Douglas R. Schotland Architect, LLC 2025