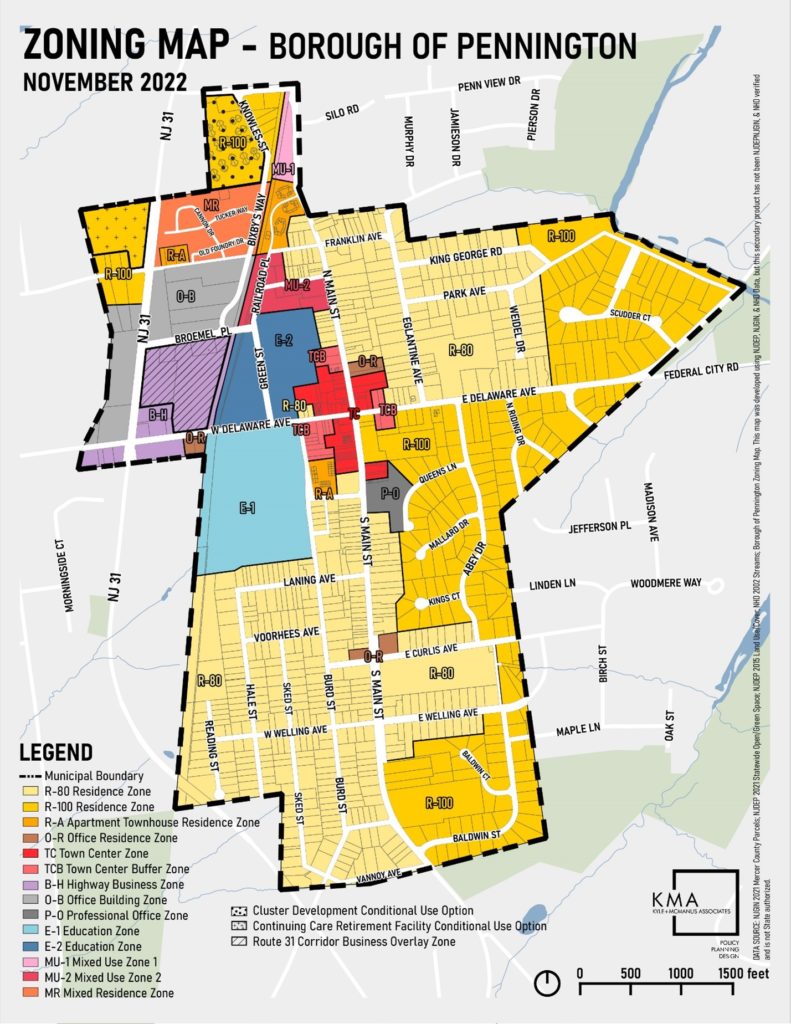

Zoning regulations tell you how you can use and develop your property. In our last post, we explored the risks of buying a property or starting a project without a clear understanding of the zoning constraints. As a review, here are three examples:

Investing in architectural services only to learn that you cannot execute the plan without a variance.

Buying a property for a certain purpose, such as operating a business, and then finding out that zoning regulations prohibit the use in that location.

Finding out that your recently purchased property does not comply with the zoning regulations, and that you cannot make any changes without zoning board approval.

Sometimes an owner cannot comply with the regulations because of her property’s unusual shape or size. Or perhaps she seeks to use her property in a way that is not permitted. In such cases, a variance may provide a solution.

A zoning variance is a special exception to the zoning regulations. It allows property owners to use their land or build structures in a way that is normally prohibited. Only a zoning board comprised of local property owners can grant a variance.

Applying for a variance can be a time-consuming and costly process. And there is no guarantee of success. That’s why it’s essential to know the “lay of the land” before you buy a property or plan a project!

As you will soon learn, there is no easy answer to that question. Because all properties and development proposals are unique, we must consider each one individually. Before we tackle this somewhat complicated subject, let’s take a few steps back and review some zoning terminology and basic concepts. (You also might want to refer to the first article in this series.) Along the way, we’ll look at specific situations where you may — or may not — need a variance.

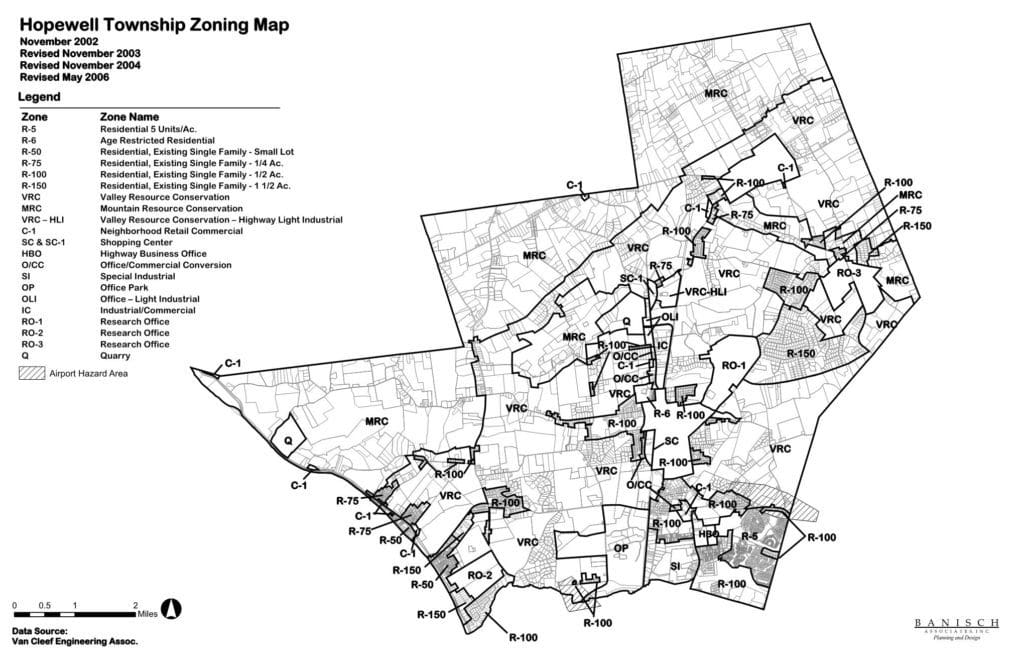

Nearly every town and city in the United States has a zoning ordinance. A zoning ordinance is a compilation of local land use regulations. A municipality may have several zoning districts, each with its own rules. Zoning regulations dictate the size and shape of buildings and lots. They regulate the relationship of a building to its own lot lines and to neighboring properties. And they also specify which uses are allowed and which ones are prohibited in each zoning district.

These regulations have many purposes. Generally speaking, communities use zoning ordinances to create the kind of built environment their residents want to live in. Naturally, the goals vary from place to place. Some might aim to create order and support their residents’ health and safety. Others might seek to protect natural and historical resources and manage growth.

Nonconformities are violations of the zoning ordinance.

Zoning ordinances are a relatively recent development. Many towns and cities did not adopt them until the late 20th century. By that time, most of the municipalities in old states like New Jersey were “built out.” For that reason, historic towns in particular have large numbers of nonconforming buildings, uses, and properties.

Some examples: An historic house with exterior walls on the property lines, where zoning regulations require a five foot setback. A 200 year-old warehouse in the heart of a downtown shopping district. A 22 ft wide lot in a zoning district that requires 80 ft wide lots.

Here’s where things get interesting (for me, anyway).

A nonconforming use, building, or lot is one that existed lawfully prior to the adoption or amendment of the zoning ordinance that made it nonconforming. These so-called “grandfathered” nonconformities may remain unless they change in character or extent. Example: If an owner sells his functioning industrial building in a retail zoning district, the buyer can continue to use it in the same manner, without any special approvals.

Suppose the owner of a nonconforming use, building, or property wishes to make changes. The new work or use must typically comply with current zoning requirements. Most ordinances have established standards and procedures for dealing with such situations. The three most common ones are enlargement, reconstruction, and substitution.

Zoning ordinances usually restrict the enlargement, expansion, or extension of a nonconforming use because it is contrary to the intent of the ordinance. Any enlargement or expansion entrenches that use. The goal of the ordinance, however, is to phase out non-permitted uses. Example: A factory predating the zoning ordinance is located in a residential district. Its owner wants to enlarge the building and expand manufacturing activities on that site. A zoning board has to approve such a change.

Likewise, zoning ordinances generally restrict the enlargement, expansion, or extension of nonconforming structures. Increasing the degree of nonconformity in this way exacerbates an undesirable condition. It’s worth noting that “increasing the degree of nonconformity” is an ambiguous term.

In some cities, this means further reducing a nonconforming setback or increasing a structure’s already nonconforming height. Example: The front stoop of an historic house is 15 feet from the property line; the ordinance requires a 20 ft setback. Building a new porch that would reduce the front setback to 10 ft would require a variance, however the regulations would allow an owner to replace the stoop with a porch that maintains the 15 ft setback.

According to an alternative interpretation, “increasing the degree of nonconformity” means expanding the area, height, or volume of a nonconforming structure. Example: The ordinance would allow the owner of the house described above to replace the stoop with a porch of the same dimensions. However, the owner would need a variance to replace the stoop with a porch that is twice as wide but maintains the existing 15 ft setback.

Most ordinances prohibit the reconstruction of a severely damaged nonconforming building. Keep in mind that ordinances can define the degree of damage in many ways. A municipality’s ordinance should clearly spell out the method used. This approach encourages the owners of severely damaged nonconforming buildings to replace them with conforming ones. Example: If a building that exceeds the allowable height suffers minor damage in a storm, it can be repaired to its prior condition. If a tornado destroys the same building, however, its replacement would have to comply with the height limit.

Ordinances often allow the substitution of one nonconforming use for another if the new use is more conforming. The logic here is that the new use could nudge a property into alignment with district requirements over time. For example, a real estate developer buys an old factory in a single-family residential zoning district. He intends to convert the building to loft apartments. Even though multi-family residential is not an approved use in that district, a zoning board may allow that change because the new use is more nearly conforming than the current one.

The local zoning officer enforces rules related to nonconformities. If you are considering changes to a nonconforming property or use, familiarize yourself with the applicable requirements. Read the ordinance and speak with your zoning officer about the details of your property’s nonconforming status.

It depends. If you’ve made it this far, you now understand how complicated zoning issues can be.

The key takeaway here is this: It is important to do your due diligence before buying a property or investing in the design of a building. You should begin by consulting a professional who is experienced with complex land use matters.

In our next article, we will explore New Jersey’s Municipal Land Use Law (MLUL) and the two variance categories it recognizes: the “C” or “bulk” variance, and the “D” or “use” variance.

If you are getting ready to buy a vintage (pre-WWII) home and are thinking about a major renovation or addition, we encourage you to contact us.

Most architects will eagerly launch into design services without carefully establishing the groundwork for the project. We offer a unique pre-design service that explores the objectives, requirements, constraints, and potential roadblocks for your project. We call it the “Vision and Strategy Review” (VSR). The VSR is so valuable because it minimizes your risk of faulty design decisions. And in the long run it can save a great deal of time, money, and frustration. Please click here to learn more about the VSR.

300 Witherspoon Street, Suite 201, Princeton, New Jersey 08542

609.737.6444

© Douglas R. Schotland Architect, LLC 2025