Congratulations! After months of going to open houses and searching online, you’ve finally found the property of your dreams. You’ve negotiated a fair price with the seller, you have a mortgage commitment in hand, and the home inspector has given it a clean bill of health. Your patience and tenacity have paid off. Yep, this one’s a keeper!

If you’re like most people, though, it won’t really be yours until you’ve customized it a bit, right? Or maybe a lot. Perhaps you’ve fantasized about a larger kitchen, or an addition with views to the surrounding landscape. It’s an exciting moment. The possibilities are limitless!

Or are they?

Whether this is your first real estate purchase or your fifth, you may not realize that owning a property does not entitle you to make whatever changes you like. Far from it. Or maybe you have a sense that there are rules, but you don’t know what they are or where to find them, or even what questions to ask.

The fact is, there are countless laws and regulations – mainly municipal, county, and state – that tell you what you can and cannot do with “your” property.

“Fools Rush in Where Angels Fear to Tread.”

Alexander Pope, c. 1711

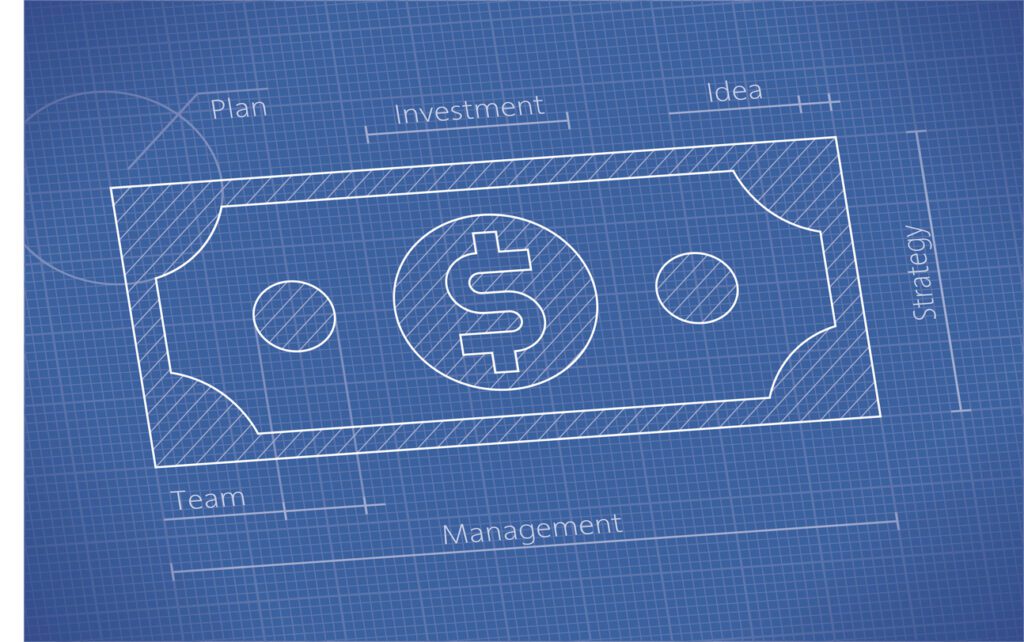

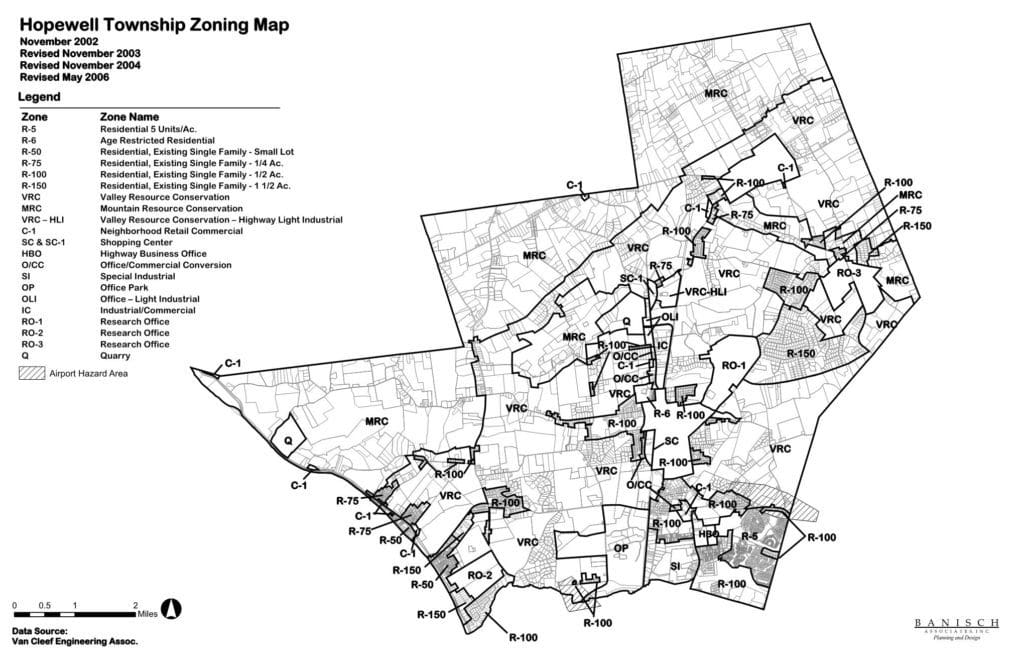

Constraints, in this context, are limitations on your ability to make changes to your property. Local zoning laws are the ones most likely to affect your plans.

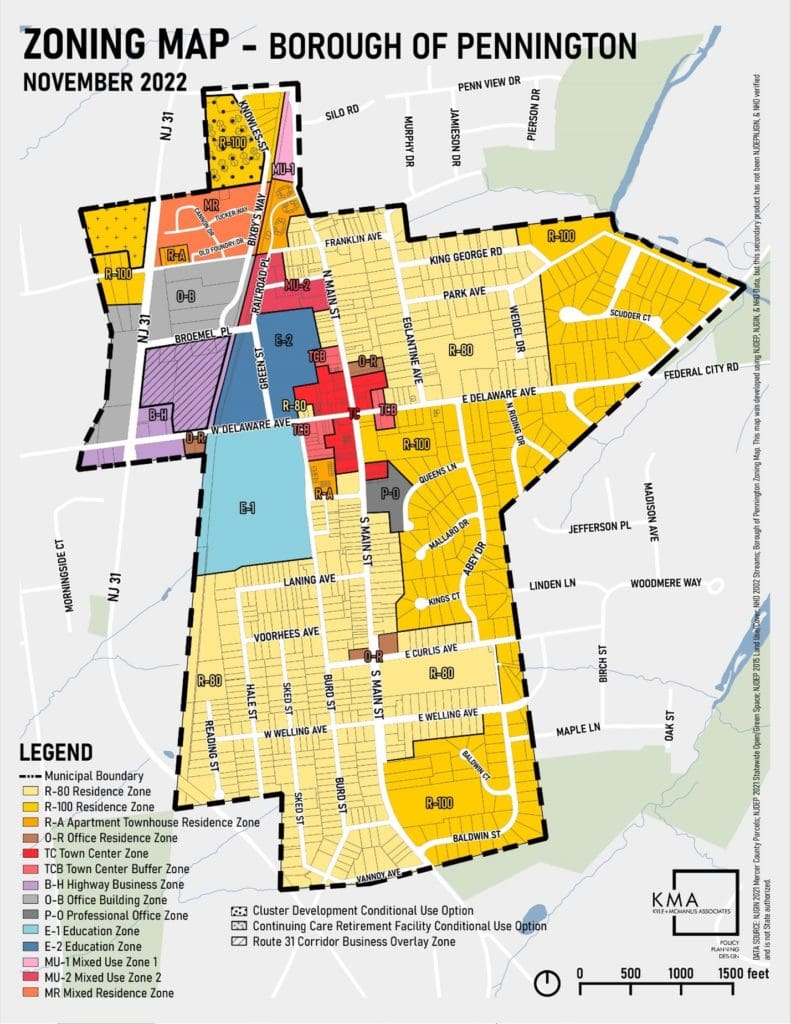

Every property has unique constraints that relate to its physical features and the zoning laws of its location. Constraints are especially common in older towns with a large number of structures built before zoning ordinances were adopted. Local examples include Princeton, Pennington, and Hopewell.

Not knowing the “lay of the land” in your community can turn a dream project into an expensive and frustrating nightmare.

Zoning laws are the most common form of land use regulation in the United States. They have been widely used since the mid-20th century. Most towns and cities—the notable exception being Houston, Texas—have a zoning ordinance that contains land development rules.

There are many.

At their core, towns use zoning rules to create communities that satisfy their residents’ needs and goals–and protect their interests. Some say their main purpose is to maintain property values.

Zoning rules may protect important natural and historical resources or ensure that property uses that may jeopardize the health and safety of residents are far from residential zones. They typically seek to protect residents’ access to fresh air and natural light, not to mention their right to privacy.

Zoning laws can also help communities to establish and maintain their architectural character, manage and direct growth, encourage economic development, and change with the times. In recent years, many cities and towns have included sustainability and climate change-related goals in their ordinances.

A city’s zoning officer has the authority to approve projects that conform to the use and bulk regulations of their zone. These projects are called “as of right.”

Applications that do not conform to zoning regulations may require a “variance.” A variance is a request to deviate from current zoning requirements. If granted, a variance permits a property owner to use his or her land in a manner not otherwise allowed by the zoning ordinance. It is not a change in the zoning law. Instead, it is a specific waiver of certain zoning ordinance requirements.

While the procedures vary from one town to another, a public meeting or “hearing” is usually required to review a variance application.

In such meetings, residents can ask questions about a proposed project and publicly support or oppose it.

After considering all of the testimony presented in the hearing, a zoning or planning board comprised of local citizens votes to approve or deny an application.

Typically, variances are granted when the property owner can demonstrate that existing zoning regulations present a practical difficulty in making use of the property.

For simple applications, a board may take a vote after one or two hours of discussion. For complex or controversial applications, however, a board might request revisions and consider testimony for months or even years before rendering a decision.

This is only an introduction to modern zoning laws. Zoning can regulate a wide range of other details, such as the amount of off-street parking required for new homes or offices; building lighting and landscaping; and outdoor signage.

By now, it should be clear that zoning laws have a significant impact on a town’s appearance and character.

And it should be equally clear that your community has a great deal to say about what you do with “your” property.

In our next post, we will dig a little deeper into New Jersey zoning laws, and we’ll explore whether you’ll need special approvals to build your project.

If you are getting ready to buy a vintage (pre-WWII) home and/or are thinking about a major renovation or addition, we encourage you speak with us first.

Unlike most architects, who will eagerly launch into design services without carefully establishing the groundwork for the project, we offer a unique pre-design service that explores the objectives, requirements, constraints, and potential roadblock for your project. We call it the “Vision and Strategy Review” (VSR). The VSR is so valuable because it minimizes your risk of faulty design decisions. And in the long run it can save a great deal of time, money, and frustration. Please click here to learn more about the VSR.

300 Witherspoon Street, Suite 201, Princeton, New Jersey 08542

609.737.6444

© Douglas R. Schotland Architect, LLC 2025